SIGNIFICANT PENDING DESIGN PATENT APPEAL: RANGE OF MOTION v. ARMAID

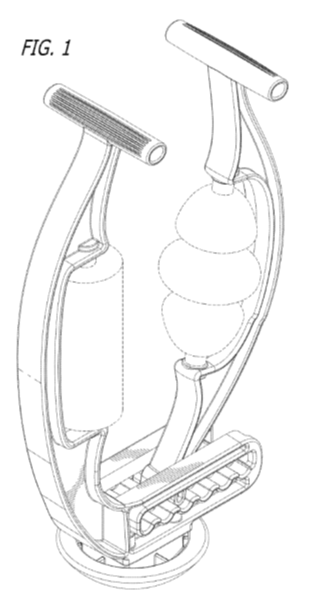

In a design patent case that’s been pending for quite a while, and which has been fully briefed and argued, the patentee Range of Motion Products, LLC (“RoM”) is asking the Federal Circuit to reverse the district court’s summary judgment order that its patent (D802,155) is not infringed by the defendant Armaid Company, Inc. (Federal Circuit case no. 23-2427). The D‘155 patent is for a “Body Massaging Apparatus”, a perspective and side view of which are shown below:

Although there are several issues in the case, I’m going to focus on two. First, claim construction including the treatment of “functional” (more properly called “utilitarian”) features, and second, the court’s finding of non-infringement.

In an earlier blog, I discussed the district court’s denial of RoM’s motion for a preliminary injunction, which was based on some of the same issues in this appeal.

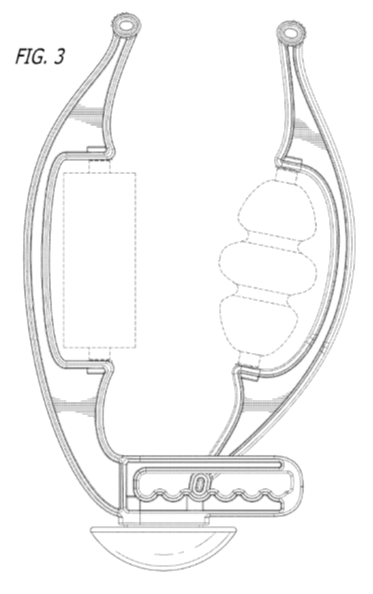

Here are illustrations of the patented and accused designs side by side:

The Federal Circuit in Egyptian Goddess, in discussing claim construction, preached the virtue of non-verbal construction of design patent claims, i.e., a preferred claim construction would be “The ornamental design of a gizmo, as shown and described.” However, the Court also said that a court could also distinguish “between those features of the claimed design that are ornamental and those that are purely functional”.

This led to a series of cases where courts tried to separate ornamental and “purely functional” features. Of course, there is no such thing as a “purely” functional feature. The Federal Circuit tried to lay this impossible task to rest in the 2015 and 2016 cases of Ethicon v. Covidien and Sport Dimension v. Coleman. But some courts refused to get the message.

In its argument, RoM quite properly noted that “all utilitarian features have an associated appearance and that appearance can be claimed in a design patent.”

That sentence – which is absolutely true - should eliminate 95% of the “functional/ornamental” problems in design patent claim construction. In other words, if all utilitarian features have an appearance that can be properly part of a design patent claim, and the non-utilitarian, i.e., ornamental features can also (obviously) be properly claimed, then nearly every design patent claim construction can simply be what the Court recommended in Egyptian: “The ornamental design of a gizmo, as shown and described.”

Nothing more need be said.

This analysis is supported by my paper: “A Primer on Design Patent Functionality”, 36 Berkeley Technology Law Journal 47 (2021).

RoM on appeal argued that the district court, among other things, improperly eliminated the appearance of entire structural features illustrated in the drawings, which ignores the Federal Circuit’s precedent in its 2015 and 2016 decisions in Ethicon and Sport Dimension.

The lower court construed the ‘155 patent claim as follows:

“The ornamental design for a body massaging apparatus, as shown and described in Figs. 1-8, except the base and the two arms, which are functional and not ornamental.” (emphasis added).

RoM quite properly noted that a very similar claim construction was rejected in the Sport Dimension case which the Federal Circuit reversed on essentially the same basis. To wit, the claim construction in Sport Dimension was:

“[t]he ornamental design for a personal flotation device, as shown and described in Figs. 1-8, except the left and right armband, and the side torso tapering, which are functional and not ornamental.” Sport Dimension at 1321. (emphasis added).

The Federal Circuit in Sport Dimension held that “the elimination of these functional elements [from] “the ultimate claim construction…runs contrary to our law”.

The Court in Sport Dimension also noted that the district court had relied on PHG v. St. John Cos. that set forth four factors to be considered in determining functionality. By the way, the only precedent in PHG for these four factors was the Berry Sterling case that set forth these factors in dicta at the end of its opinion. These factors, as I have also pointed out in previous papers, are curiously akin to the factors that are considered in trade dress analysis, suggesting poor legal research on the part of whoever wrote the Berry Sterling opinion, since the underpinning of trade dress functionality is distinctly different from functionality of design patents.

The PHG factors were indeed discussed in Sport Dimension, and the Court in that case agreed with the lower court’s analysis of same. But, significantly the Court in Sport Dimension went on to say:

“Nonetheless, even though we agree that certain elements of Coleman’s design serve a useful purpose, we reject the district court’s ultimate claim construction. As in Ethicon, the district court’s claim construction fails to account for the particular ornamentation of the claimed design…”

In RoM, the district court nevertheless analyzed the claimed design using the PHG factors, and concluded: “[I]t is evident that many of the [claimed design’s] individual features have a functional purpose and, thus, are beyond the scope of the claim in the D’155 patent.”

Ignoring Sport Dimension and Ethicon, the district court then said that it would be “impossible” to discuss which features of a design patent are driven by functional considerations “if every feature depicted in solid lines in design patents were per se ornamental”.

It appears that the court’s claim construction was way off.

INFRINGEMENT

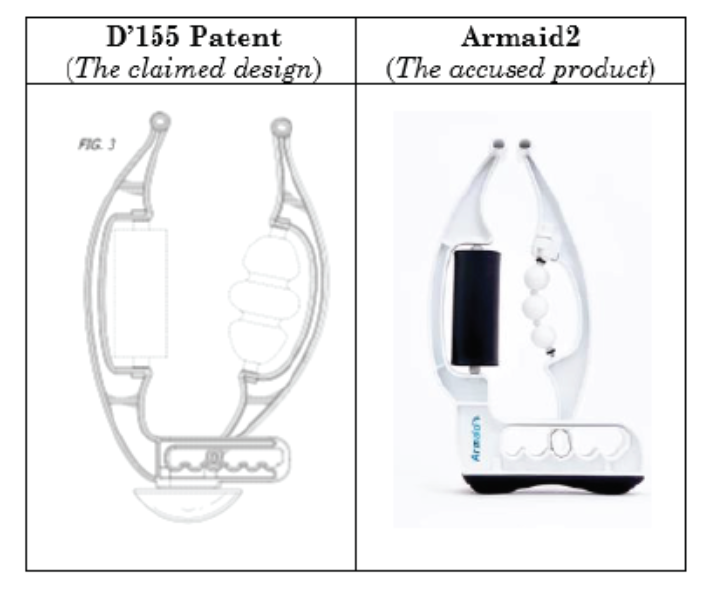

The court went on to compare images of the D’155 patent to the accused product and the closest prior art:

The court once again ignored the appearance of certain utilitarian features, saying: “These functional features are not protected by the D’155 patent and, therefore, do not bear on the ordinary-observer test.”

After noting several differences between the two designs (there are always differences between a patented and accused design, without which the case would not be in court) the court found them “plainly dissimilar” (a/k/a “sufficiently distinct”). I have ranted and raved about the impropriety of the “plainly dissimilar” test as obviously subjective in determining infringement. See my earlier blog post on the subject.

The district court nevertheless proceeded to compare the patented design, accused design, and the prior art. In doing so, it basically repeated its analysis under the “plainly dissimilar” test, finding a number of differences (which are always present) and once again, concluded that “[T]he D’155 patent and the Armaid2 (accused design) are plainly dissimilar or, at the least, not substantially similar.”

It is quite clear that a jury, consisting of a group of ordinary observers (as found in the Braun v. Dynamics case), could easily conclude that the claimed design and accused product are much more similar to each other than each is to the closest prior art, which would make a finding of infringement more likely than not.

RoM also argued that these disputed issues of fact should have precluded summary judgment, and allowed those issues to be decided by a jury. The court dismissed RoM’s argument by saying that claim construction, even though having “evidentiary underpinnings, how to construe a claim is a question of law within the exclusive province of the court”. But, obviously, those “evidentiary underpinnings” were in dispute and should not have been resolved by the court.

I have reviewed the defendant’s brief on appeal and find it non-persuasive, relying in large part on the Federal Circuit’s disastrous opinion in Lanard Toys Limited v. Dolgencorp LLC, Ja-Ru, Inc., and Toys “R” Us-Delaware, Inc. (see my earlier blog post about that case), and irrelevant portions of the Sport Dimension and Ethicon cases, both of which clearly hold that utilitarian features have an appearance that must be taken into account in claim construction.

Here are RoM’s opening Appeal Brief, Armaid’s Response, and RoM’s Reply.

I wait for the Court’s decision with bated breath.

Meanwhile, you decide.