DESIGN PATENT OWNER GETS PEPPER-SPRAYED

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on December 11, 2020 handed down Super-Sparkly Safety Stuff, LLC, v. Skyline USA, Inc. (Case No. 2020-1490). In a non-precedential opinion, the Court reviewed de novo the lower court’s decision granting summary judgment of non-infringement. The Court found no infringement under the ordinary observer test in that the patented and accused designs were “plainly dissimilar” and “sufficiently distinct”, which did not require consideration of the prior art. Even if not “sufficiently distinct”, the Court found that there was no infringement when taking into account the prior art as commanded by Egyptian Goddess. The design claimed in the asserted U.S. Pat. No. D731,172 was for a “Rhinestone Covered Container for Pepper Spray Canister”.

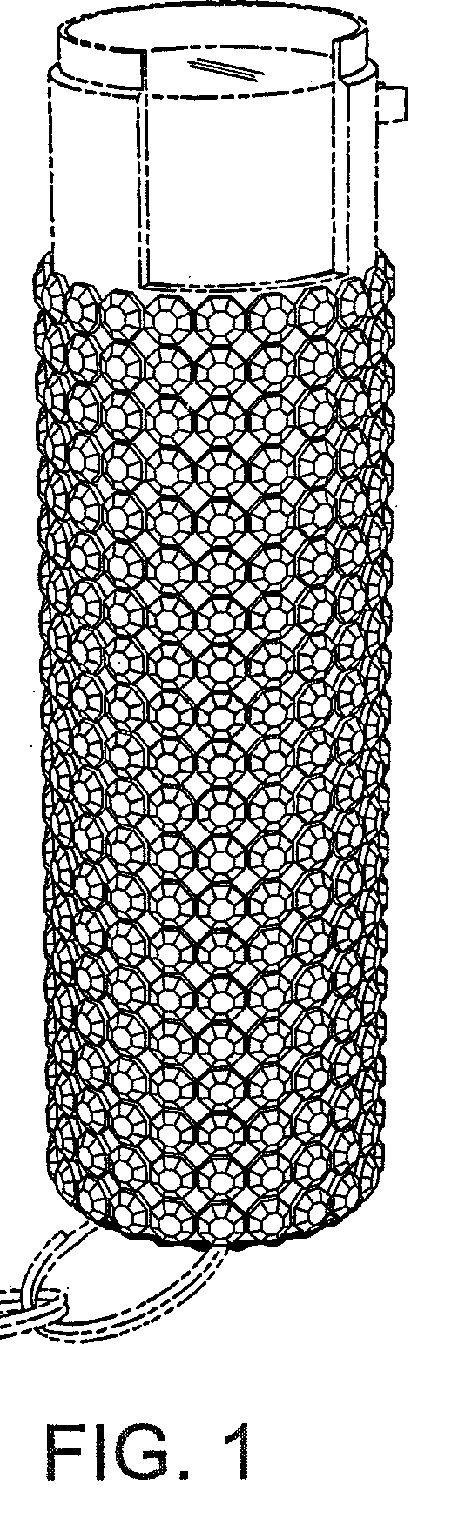

Below are illustrations of the perspective and bottom views of the ‘172 patent, the accused design, and the closest prior art “Pepperface”.

PATENTED DESIGN

PATENTED DESIGN - BOTTOM VIEW

ACCUSED DESIGN

PEPPERFACE PRIOR ART

The parties had agreed that the difference between the patented and accused designs was that the former claimed the rhinestones on the bottom of the canister, whereas the latter did not. The Court found that removing the rhinestones from the bottom surface was a “significant departure” from the claimed design, resulting in sufficiently distinct designs even when not considering the prior art.

Then the Court admitted that there were not many examples of prior art designs, but nevertheless the prior art Pepperface reference had rhinestones “around the majority of the canister”, but not on the bottom. Citing Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, the Court then said:

“[The] attention of a hypothetical ordinary observer conversant with bedazzled pepper spray canisters would be drawn to the presence or absence of rhinestones on the bottom of the cylinder.”

This is reminiscent of the old “point of novelty” test that was abolished by Egyptian Goddess. That is, the Court essentially said that having rhinestones on the bottom was the point of novelty that distinguished the patented design from the prior art, and since the accused design did not have that point of novelty, there was no infringement. It did appear that rhinestones on the bottom was indeed novel, since it was not found in the Pepperface prior art, nor the closest prior art of record, U.S. Pat. No. D667,999. So, are we now reverting to the old Litton “point of novelty” test?

Another significant point is this. This case was decided on summary judgment, i.e., the court concluded that there were no material facts in dispute, meaning no reasonable jury could find in the non-movant’s (i.e., the patentee’s) favor. But is that true?

I have previously ranted and raved about the unfairness of a “sufficiently distinct” finding that allows a court to ignore the prior art. For one thing there’s no objective way for a court to determine whether two designs are sufficiently distinct, and for another, there’s always prior art that’s relevant to the infringement analysis. A court finding that a patented design is “sufficiently distinct” from an accused design effectively steals the patentee’s right to a trial by jury on the ultimate issue of infringement. Whether the prior art is closer to the claimed design or accused design is a question of fact, ideally suited for a jury. A holding by a court on summary judgment that the two designs are “sufficiently distinct” prevents this question from ever coming before the jury.

Moreover, in this case, it’s not so clear that the patented and accused designs were not substantially the same in overall appearance. In the ‘172 patent, the rhinestones cover the canister all the way to the bottom edge, as they do in the accused product. However, in the Pepperface prior art, the rhinestones only cover a portion of the outer cylindrical surface of the canister; the rhinestones are centered on the cylinder, leaving exposed portions of the cylinder both at the top and bottom. Surely, in light of the fact that the rhinestones in both designs extended all the way down to the bottom, a jury could find that the patented and accused designs are closer to each other in overall appearance that either is to the Pepperface prior art, in spite of the differences on the bottom of the canisters.

Indeed, what is the difference between the bottom not having rhinestones and a portion of the cylindrical surface of the canister not having rhinestones? Either way, rhinestones are missing.

The court did not mention the prosecution history of the ‘172 patent. It reveals that the examiner found that the application disclosed 4 embodiments (Figs. 1-5, 6-8, 9-11, and 12-14). Each of these embodiments claimed a different length of rhinestones on the outer surface of the cylindrical canister. The examiner concluded that the 4 embodiments were patentably indistinct, i.e., basically the same, commenting that “the differences between the appearances of the embodiments “are considered minor”. Clearly, if the 4 embodiments are basically the same, even if they have a different length of rhinestones on the exterior, an argument could have been made that they are basically the same as the accused design. The absence of rhinestones on the bottom - had it been claimed - would very likely have been considered by the examiner to be basically the same as embodiments that had rhinestones on the bottom. Since “basically the same” is virtually indistinguishable from the “substantially the same” test for infringement, the prosecution history made out a plausible argument for a finding that the defendant’s design infringed the ‘172 patent.

It could also be argued that the ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives (as required by Gorham and Egyptian) would pay scant attention to the bottom of the canister rather than the exterior cylindrical surface. After all, it’s the exterior surface that gets advertised, noticed at the point of sale, and held by the user (note that of the 6 illustrations in the Pepperface ad, none showed the bottom of the canister). It could easily have been found by a jury that the exterior cylindrical surface is the dominant visual component noticed by an ordinary observer “giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives”, who may not even notice whether the bottom is covered with rhinestones.

In reviewing past case law, little attention has been paid to the Gorham and Egyptian requirement to consider what a purchaser would do, in contrast to the clear wording of the test for infringement:

“[I]f, in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other.” (emphasis added)

Thus, in analyzing infringement there should be an inquiry into what attention a purchaser usually gives when buying a product. For example, when buying a refrigerator or TV, does the purchaser pay attention to the bottom, sides or back of the product? Even if those elements may be claimed, they are generally not dominant features viewed by a purchaser who would likely focus on the front of the product. Does a purchaser pay attention to the visual appearance of the insoles of Crocs shoes (see Int’l Seaway)? Does a purchaser pay attention to the visual appearance of the bottom of a shrimp container (see Contessa)? Would a purchaser pay attention to the top of a ceiling fan (see Fanimation)? These are legitimate inquires under both Gorham and Egyptian, yet the cases are silent about this requirement.

It is curious that the accused infringer was represented by Robert Oake, the same attorney who represented Egyptian Goddess back in 2008. This time, Mr. Oake was arguing non-infringement, while in Egyptian he was arguing infringement. While Egyptian was very significant regarding the issues of design patent claim construction and the abolishment of the point of novelty test, the patentee nevertheless lost on the merits. Its patented nail buffers, having pads on 3 of the 4 sides of an elongated, square, hollow body, was found not to be infringed by a nail buffer having exactly the same elongated, square, hollow body but with 4 pads, one on each side, instead of 3 as in the claimed design. The patented and accused designs in Egyptian, and the closest prior art, are shown below:

EGYPTIAN GODDESS

Note the following: the patented and accused designs are both elongated rectangular, hollow squares having pads on their sides; no prior art reference taught that appearance. The Falley reference was solid with no pads. The Nailco reference was elongated and hollow, but triangular. Even though Nailco has pads on all 3 sides, any ordinary observer would see that the patented and accused designs are closer to each other than to the Nailco prior art. Whether one of four pads was missing or not is relatively minor, and is probably not visually important to an ordinary purchaser. Three vs. four pads may be important functionally, but visually the two designs could easily be found substantially the same in overall appearance. What did the Federal Circuit say in Egyptian?

“[U]nlike the point of novelty test, the ordinary observer test does not present the risk of assigning exaggerated importance to small differences between the claimed and accused designs relating to an insignificant feature.”

Yet, in the present case, the Court did exactly that: assigned exaggerated importance to a minor difference – the presence or absence of rhinestones on the bottom of the canister, that an ordinary purchaser would likely pay little or no attention to.

The facts in Super-Sparkly are fascinatingly similar to those in Egyptian, and both cases involved Mr. Oake as counsel. And in both cases the lower court granted summary judgment motions of non-infringement. In Egyptian, one side of a design had something missing (the patented design was missing a pad), and in Super-Sparkly, one side of a design had something missing (the accused design was missing rhinestones). Maybe Mr. Oake learned from Egyptian that siding with the missing side was the side to be on!