FEDERAL CIRCUIT REVERSES GRANT OF PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION IN HOVERBOARD DESIGN PATENT CASE

On October 28, 2022, in ABC Corporation I et al. v. Ebay et al., the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reversed the lower court’s grant of a preliminary injunction. The decision was based on the patentee’s failure to prove a likelihood of success on the issue of infringement. A large portion of its opinion was based on alleged insufficiencies in plaintiffs’ expert’s report.

The plaintiffs held 4 design patents of varying scope covering its design of a hoverboard (D784,195; D785,112; D737,723; and D738,256). They accused 4 products sold by appellants of infringing each of the design patents. The court included an Appendix to its opinion showing comparisons (proffered by the appellants) of each view of each of the 4 design patents to one of the accused products (called Product D). I suggest you refer to the court’s opinon to see the various images in its lengthy Appendix.

Two of the accused products appear below:

PRODUCT D

PRODUCT A

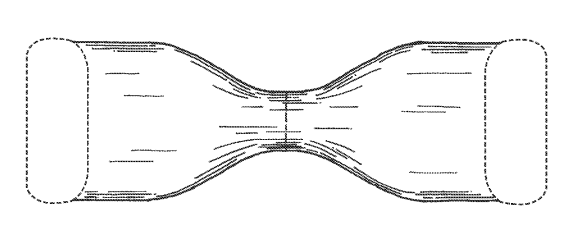

The Appendix also compared the patented designs, Product D and the main prior art reference D739,906, one figure of which is shown below:

‘906 PRIOR ART

The court characterized the prominent feature of the ‘906 prior art to be its hourglass shape.

According to the court, the expert’s report showed side-by-side images of the asserted patent and accused products and described how the ordinary observer test for infringement applied to the accused products as a group. The problem, the court said, is that the expert did not provide “a product-by-product analysis”.

As an example, the court quoted a portion of the expert report: “Unlike the cited prior art, the claimed design of the ‘195 patent and the Accused Products share an integrated hourglass body with many horizontal styling lines across the body and a relatively flat surface across the top, arched covers over the wheel area, larger radii on the front and back of the underside. Unlike any of the prior art the foot plates narrow as they extend toward the center.” (emphasis by the court). The court chided the expert for failing to explain why having an hourglass body was unlike the ‘906 prior art; this was a theme throughout its opinion.

This was a bit unfair, since the full quote from the expert’s report calls for a combination of the stated elements, rather than a list of individually unique elements (note the expert’s use of the word “integrated”). This is in accordance with the generally accepted notion that designs are to be viewed and analyzed as a whole, not dissected element-by-element. The court, in contrast, focused on the hourglass shape and never mentioned the other elements in its opinion (save in footnote 3).

However, the seminal Egyptian Goddess case did say: “When the differences between the claimed and accused design are viewed in light of the prior art, the attention of the hypothetical ordinary observer will be drawn to those aspects of the claimed design that differ from the prior art”. The court rephrased this as follows: “{W}here a dominant feature of the patented design and the accused products – here the hourglass shape – appears in the prior art, the focus of the infringement substantial similarity analysis in most cases will be on other features of the design. The shared dominant feature from the prior art will be no more than a background feature of the design, necessary for a finding of substantial similarity but insufficient by itself to support a finding of substantial similarity.”

This analysis, focusing on a single element as a “dominant feature”, seems to go against the expert’s “integrated” approach where he did not dissect the claimed design. It also raises another concern, namely whether the court, not an expert in design, is qualified to conclude that a particular design element is “dominant”.

The court also criticized the district court in failing to apply the ordinary observer test on a product-by-product basis, which it said was particularly important in this case in light of the significant differences among the accused products.

Regarding the need for analysis product-by-product, the court said: “Even a cursory review of the four accused products shows that they are different from each other, display features not found in the asserted patents, and lack features shown in the asserted patents.”

This is no big surprise, since cases where an infringer exactly copies a patented design normally settle (the noted exception being Samsung’s behavior in Apple v. Samsung, a behavior that eventually cost it several hundred million dollars despite winning its appeal in the Supreme Court).